Raya Bruckenthal

Welfare of the Monarchy

Art Cube Gallery

Artists' Studios, Jerusalem

Sep. 2016 - Jan. 2017

The prayer “for the welfare of the monarchy” (Shlom Hamalchut) is found in Jewish prayer books from the 13th century on. It was recited mostly by the Jews of Diaspora, who prayed for the welfare and prosperity of the ruler in the territories where they lived, as a token of their loyalty to him. The prayer lends its name to a solo exhibition of Raya Bruckenthal’s which looks at the Belz Hasidic community in Jerusalem, examining its visual and stylistic codes as a case study of Hasidic aesthetics at large. The concept of the welfare of the monarchy – or government –has been accompanying the Hasidic movement since its beginnings, in the 18th century, and attests to its deep ties to a monarchic worldview. Harboring nostalgic longing for pre-modern forms of government, it encapsulates an anachronism inherent in the Hasidic movement, veering between an ‘old world’ and a new one.

As in many other Hasidic courts and affiliations, the Belz community draws its hierarchic structure from this monarchic worldview. The analogy between god and believer on the one hand, and a king and his subjects on the other, is a common trope in Judaism, dating centuries back; in Hasidic courts, however, the monarchical model is applied to aspects of secular life as well – the organizational structure of the community and everyday life. Such communities are led by an Admor – the highest presiding rabbi, who in the Hasidut’s early days was referred to as tzadik (‘rightuous’) – a charismatic figure who assembles a court of followers around him.[1] In addition, to insure the continuity of the community’s spiritual leadership, the title of Admor is passed on from father to son, just as in monarchical dynasties. This spirit is still alive in the Belz community today, both in the spiritual sense and from the political-organizational aspect. The Admor is regarded as a sovereign whose authority is beyond question, while community members are seen as his subjects. He is at the head of a social unit that would see itself as a self-run autonomy – especially as regards the hegemony of the larger orthodox movement, of which it is part.

But how did this monarchic-like relationship between the Admor and his community come to establish itself? The roots of the Belz ethos and hierarchy can be traced back to its history in the Hungarian and Galician territory, where it stood as one of the most dominant and influential Hasidic courts prior to World War II. Though nearly decimated during the holocaust, the community managed to rebuild itself in Israel in the course of a single generation, owing to a charismatic leadership that managed to reignite the spirit of faith and self-assurance among its few remaining followers.[2] The community reshaped itself along the lines of the orthodox worldview – that is, by tightly adhering to former Eastern-European customs and traditions: from holding on to the name of Belz, the city where it originated, to the manner of dress, way of life, and of course the Yiddish as the major spoken language.[3] At the heart of the Belz ethos there emerged a narrative of ruin followed by rebirth, with – alongside a solemn and momentous rhetoric of infinite mourning and loss – a celebration of the community’s survival and victory over a its Nazi archenemy, who all but decimated it. With the community’s population nowadays at several thousand families,[4] Belz is regarded as a major power in the ultra-orthodox sector in Israel, and surely within the Hasidic movement itself. This achievement is largely to the credit of its current Admor, Rabbi Yissachar Dov Rokeach the second, who put in place an elaborate network of community charities and welfare institutions that benefit adherents – the members of the Belz community.[5]

* * *

Running deep in its rhetoric and hierarchy, the association to themes of regalia and majesty should be seen, therefore, as a reflection of the Belz Community’s ‘renewed strength’. This is evident not only in its administrative and political structure, but likewise in the community’s visual language and graphic identity. In her Welfare of the Monarchy, Bruckenthal attempts to examine this visual language across features of style and iconography, including the mostly-European traditions of style and ornamentation it draws on. Despite the old-world appearance of many of its insignia and visual features – both austere and lavish at the same time – these symbols are, in fact, the products of a vibrant, still evolving visual language that continuously draws on further styles and graphic idioms; and the more it evolves, the more it hardens into something of an overall “stylistic authority”, whose influence goes beyond the Belz community proper, reaching growing circles in Israeli orthodoxy in general.

The Belz aesthetic manifests itself the most on two levels in particular: in the monumental architecture of the Belz Great Synagogue, in Jerusalem, and in the design and typography of printed matter and logos – the various publications, invites, banners, insignia and more. In both cases, the features and forms draw on an existing repertoire of emblems designed to represent the noble rule of a sovereign – an old world of prestige, honors and majesty. They are marked by their ornate solemnity and rigor, as befits the status and rhetoric of community leaders who see themselves as the heads of an autonomous societal unit – whether spiritually, administratively or politically.

Undoubtedly, the epitome of this symbolic “branding” is embodied by the great synagogue, an overwhelmingly grand structure erected in the midst of the Kiryat Belz neighborhood, in Jerusalem, whose massive presence dominates the entire landscape of the city’s north. Inaugurated over a decade ago, the complex was built following the instructions of the incumbent Admor, with a design that is meant to echo the presumed architecture of the Second Temple as well as the original synagogue of the community’s, in the small city of Belz (nowadays in Ukraine); now destroyed, stones from the original building were combined in the structure of the great synagogue, to symbolize the community’s endurance and continuity. The building functions as the spiritual and political center of the community, and it houses, in a system of ten levels located underneath the gigantic prayer hall, study halls, additional prayer rooms, a memorial for holocaust victims of the community’s, canteens, reception halls, ritual immersion bathes, guest houses, a bakery and a central kitchen. The Admor’s residence and offices are located at the edge of the complex, connected to the main prayer hall by a roofed passage.[6] In front of the synagogue is a large square for public gatherings on holidays and other special occasions.

The opulence reaches its peak in the main prayer hall – which, despite the vastness of its proportions, distinguishes itself by the minute elegance and refined craftsmanship of its furnishings.[7] Sitting some 10,000 devotees, the hall is equipped with advanced acoustic technology; nine grand crystal chandeliers hang from its ceiling, especially-built for this hall; the Torah ark, at the eastern end of the hall, was crafted from imported wood and is covered by a sumptuous parochet. By its style, dimensions, the quality of its craftsmanship and the richness of detail, the building stands as the embodiment of Belz’s renewed strength and glory – a community that rose up from the ashes of its devastation in Europe to stand up on its feet again, after the loss of so many of its sons and daughters.

An expression of the community’s ‘renewed strength’ is likewise observable in the paraphernalia of graphic design – however more subtly: in the symbols of kosher stamps, the emblems of educational institutions and community bodies, and in the many invites, street banners and insignia, all of which are designed as variations on the logo of the Hasidic court itself, designed back to the 1970s. Both ornate and rigorous, the designs borrow from European styles of decor and embellishment from the renaissance to the rococo; also discernable are oriental and Israeli influences. Despite their grave and anachronistic appearance, the emblems are part of a contemporary language of visual communication, and are aimed at lending status and prestige to political entities in the present. The Belz language of visual communication started developing informally some 25 years ago, in private graphic design studios. In its mix of styles and epochs, it is a clear example of eclecticism in design; the visual motives it appropriates – gleaned from former periods for the status and rigor they convey – are taken out of context and reintegrated in a new and comprehensive visual design language which still continues to evolve and take shape.

* * *

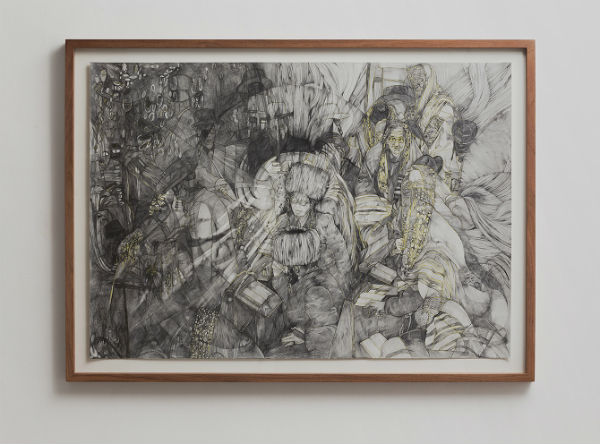

Welfare of the Monarchy is presented across two exhibition spaces simultaneously, in the Art Gallery of the Artists’ Studios in Jerusalem and in Bruckenthal’s own studio, on the same floor in the building. The multiple display points to a twofold, complimentary artistic undertaking. The works on display at the gallery – a video, a wall installation and a work in drawing – raise questions on the prevalence of majestic imagery in the devotional context, pointing out mechanisms of holly service; while based on an existing repertoire of images, they forge new fictional narratives from them, which foregrounds aspects of religious dedication and devotion. The gallery setting lends a public dimension to the display, all the better to address the outwardly side of worship and faith. In contrast, the work installed in Bruckenthal’s studio offers a classificatory a gesture, a functional-typological lexicon of those same stylistic idioms from which a narrative is woven in the exhibition space nearby.

The main feature of the works on show, a video titled “In All her Glory” presents a group of seminar girls engaged at assembling a large crystal chandelier. The girls, dressed in their typical seminar uniform, are visibly immersed in the work at hand and deeply dedicated to it, knowing that the chandelier shall, eventually, adorn a consecrated place of worship. The designated – and imaginary – location of the chandelier imparts a ritualistic aura on the work, as if it were some religious office. When the work is complete, dancing and chanting begins, lending ecstatic qualities to the scene. The video’s title is taken from an oft cited biblical verse – “all glorious is the princess within her chamber” (Psalms 45) – on which the rigorous standards of feminine modesty, as well as women’s exclusion from public spheres of life, is predicated. The girls in the video evidently belong to a homogenous group in terms of their age and gender, forming a “designated group“ whose status in the community owes to the dedication of its members to the task at hand, like a link in an endless chain of worship. The video lends a fantastic aura to their toiling – a group effort which nonetheless provides each with an outlet for private sensations of ecstasy and fervor. The ceremonious character of the effort lulls a lurking sense of exploitation with regard to the circumstance of the chandelier’s assembly and the place of the girls in the community’s hierarchy.

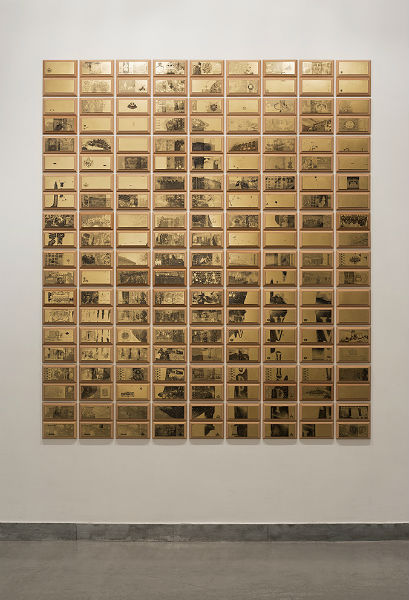

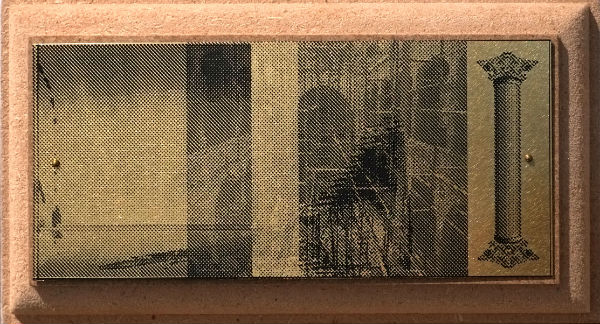

An installation titled “Donors’ Wall”, part of the works in the gallery, is comprised of 176 brass plates of variable dimensions. At first glance, it recalls a donors’ wall often seen in the foyers of public buildings, but a closer look reveals that the ensemble is essentially visual, with individual images carried across the general shape of one giant chandelier. Etched with a laser photochemical technique, the images originate in the larger repertoire of Jewish orthodoxy and that of the Belz community in particular. Each plate features its own unique composition – a layered digital collage or an enigmatic complex of images grouped together. We encounter the Belz Great Synagogue, portraits of dignitaries, a synagogue chandelier, verses from the “welfare of the monarchy” prayer and insignia of Hasidic institutions – a hybrid of images representative of community powers and trendsetters. Instances of kitsch and non-religious life are also thrown in, like the chandelier hanging at the V.I.P area of Cinema City, the Jerusalem multiplex. The profusion of visual codes harbors inner tension: on the one hand, a variety of combinations that mark each plate individually; on the other, a clamor of imagery that blurs the Jewish ideal of anonymous giving, obscuring it under layers of self-interested exuberance.

On a wall across from the installation hangs a small-format portrait of a Hasidic youth in the recognizable headgear of the Admor and his family. Meticulously executed, this realist work of drawing stresses the personalized mark of a portrait made by hand, as befits the distinguished lineage of the sitter, a future heir to the Admor. The small format, together with the work’s reserved solemnity, stands in stark contrast to the dizzying “Donor’s Wall” from across – the latter suggestive of the growing phenomenon, in ultra-orthodox circle, of a personality cult of distinguished forefathers and rabbinical figures. The influx of iconic figures that have come to adorn walls in homes and public spaces betrays an adoration of the type more commonly associated with Christianity, blurring the thin line between devotion and idolatry.

The installation “Index of Forms,” on show in Bruckenthal’s studio, functions like a creative workspace or an 'inspiration board’: tens of decorative motifs printed on A4 papers are laid out in a formal typology which maps the tastes and stylistic choices proper to Hasidic aesthetics, especially in the domains of applied arts and commercial branding. The decorative elements – such as symmetrical sets of curtains, crystal chandeliers, crowns, decorated goblets, marble columns and Torah scrolls – are marked by their ornamental visibility; mostly in silver and gold, they connote an old world of dignity, majesty, opulence and prestige. Based on decorative schemes drawn from renaissance art, baroque and rococo, their digital editing cancels out their historical baggage to leave them as empty emblems, ready to enter an eclectic repertoire of signs and hybrids assembled for the aggrandizement of the Admor and of his court of followers.

The graphic evolution of the motives occurs intuitively, rather than through a systematic, research-based methodology. The depository of forms and elements accumulates organically, and nowadays can be obtained online from image banks, for a charge. The attempt on the part of Bruckenthal’s to lay out and consolidate this repertoire ad hoc, based on research, can be read as an attempt to form a standard and comprehensive visual typology of connotative, readable signs. However, to a degree, this classificatory gesture is ironical, lacking as it does any official grounding or validity.

* * *

Through a fictional narrative that draws its inspiration from the Belz Hasidic community and its regal symbolism, Welfare of the Monarchy opens a discussion on faith, the relationships of believer and deity and the derivative mechanisms of religious service – as well as the dangers they inhere, namely that of emptying the devotional impulse of meaning. Yet above all – and from an angle that seeks to explore how ideas and values come to be visually represented – Bruckenthal draws our attention to the role that visuals play in constituting a community’s identity in the context of ultra-orthodox societies today: earthly expressions of divinity that are part and parcel of the social fabric, taking their place alongside the all-important written word.

[1] David Assaf, “Hasidism: Historical Overview,” The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, Yale University Press, 2008, pp. 659–670.

[2] Assaf, ibid.

[3] Assaf, ibid.

[4] As of 2013, the Belz population is estimated at around 6,000–8,000 families worldwide.

[5] This highly developed network of community organizations and services includes: a Badatz (a rabbinical court of justice), educational institutions for boys and girls, yeshivas for native community members and new recruits (ba’aley teshuva), a weekly magazine and various publishers, an outreach organization, a charity organization for the sick and needy, the Hidabrut outreach organization, the Kiryat Belz Committee and many more.

[6] In view of findings, it is hard not to compare the Belzer Admor with Charles the Great, the eight-century ruler of France and Germany. Whether knowingly or unknowingly, the structure of th synagogue reuses the architectural pattern as that of the Palatine Chapel in Aachen, seat of Charles the Great; and like him, the Admor too is chosen to serve as his constituency spiritual leader – god’s emissary on earth – as well as its ruler in earthly matters.

[7] In a conversation Bruenthal held with Aharon Ostreicher, the architect in charge of the building and its interior decoration, he defined the stylistic choice as a “bric-a-brac,” a “bunch of influences from all things pretty and appealing”.