Hadassa Goldvicht

An Ocean within an Ocean

Art Cube Gallery, Artists' House Jerusalem

Oct 2017 - Jan 2018

The autobiographical dimensions are central to Hadassa Goldvicht’s works. Working in visual and textual medium alike, Goldvicht draws on her private life and experiences to create work that points to an ongoing preoccupation with the family unit and parent-children relationships, among others. Whether physically or metaphorically, the corporeal dimension of the artist’s body is ever present, serving as a creative motor and an all-embracing space able to contain the charged intersection of life with the artistic gesture. This intersection between life and physically on the one hand and the day-to-day artistic practice on the other – a practice she approaches as a kind of ritual or prayer – blurs the boundaries between private and the public, removing any separation between the artist's “self” and her artistic action. Her work is hence submerged in life, feeding off of it and spilling over to it in turn in a symbiotic creative cycle. With existential concerns, anxieties and subliminal sensations brought to the surface, it is an undertaking that allows her to realize the ritualistic potential harbored in the creative process, to generate a reality while treading the thin line between truth and fiction.

The exhibition An Ocean within an Ocean, presented simultaneously at the gallery space of the Artist’s House and Goldvicht’s studio, confronts its viewers with a space of in-between, an elusive environment whose assortment of objects don’t seem to articulate, on first look, a single coherent narrative: a bookshelf unit, a slide presentation, a flickering electric switch and different items of furniture carrying video projections. Taken out of context, these objects join in a loose compound that harbors a secret. And yet, despite a hidden underlying logic that seems to connect them, they exhibit a certain kinship, a shared fate and genetic makeup. In their coexistence they bring to mind a collection of ‘mnemic traces,’ to use Freudian terminology – psychic images located somewhere between perception and consciousness, shortly before becoming representation or symbol – objects that, by their personal and utilitarian character, appear to harbor life chapters from a past that are now repackaged and stored side-by-side, anachronistically and without any clear hierarchy.

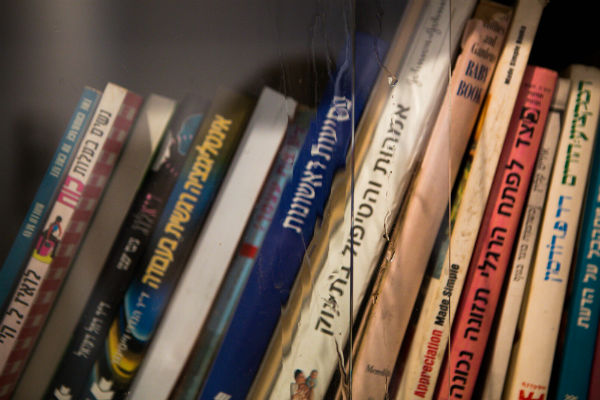

“Education (1985),” the main piece in Goldvicht’s show, comprises a standard household book cabinet. The books on its shelves seem to suggest the organic accumulation of a private library over the years, at the same time pointing to a specific time and place: the 1980s in North America and Israel, where the artist had spent her childhood. Encompassing many self help, parenting, new age and feminist theory books, the library looks somewhat dated. A hidden mechanism pumps droplets of water to the library’s upper shelves, regular pulses that drip down, soaking the books on their way and accumulating in a puddle of water that accrues around the library. The books’ encounter with the water is, obviously, a devastating one, as their entire contents – a body of knowledge that, despite the time that went by since the books’ publication, takes on still relevant questions of gender, personality, self-accomplishment and creativity – will be slowly erased irretrievably, with the books themselves becoming a formless and meaningless pulp of matter.

The ongoing erasure operated in the work brings us back to the moment before the appearance of the text – to an extent, to a pre-lingual stage. Goldvicht, who has continuously tackled language in her work over the years, examining it in the range between signification and raw substance, attempts a return to the point of departure, to a place where language isn’t but a taste, an instinctual sense perception.[1] However, this return to a pre-lingual phase is motivated not just by an attempt to go back to the thrill of the initial exposure to language – and knowledge; it also cautions against the reckless use of language when taken as a mystical code, a system containing the potential for far-reaching creation – as well as devastation.

While very personal in nature, “Education (1985)” brings to mind religious rites of cleansing, both private and collective. Through objects that carry the mark of private belongings and the unique, and gradually diminishing, body of knowledge stored in them, it points to a moment of crisis and lost opportunity. With a mixture of empathy and disillusionment, Golvicht looks back at a whole generation of women that were brought up with the ideas of third-wave feminism – of female empowerment and agency, of self-expression and accomplishment – but ended up being torn between their hopes and aspirations and having to concede to a social order that, then as now, remains male-dominated.

“A Woman's Guide to Changing the Patterns of Intimate Relationships,” an additional work in the show, is similarly based on a textual source from the artist’s library: “The Dance of Anger” by Harriet Lerner, from whose subtitle it borrows its name. The electrical switch of a heater flickers with its red light the book’s contents in Morse code, thereby operating a thorough transformation and re-encoding of its source. Published in the USA in 1986, Lerner’s bestselling book deals with feminine anger from a therapeutic and feminist perspective. The breaking down and rearrangement of the text to its most elementary semantic units delivers an ironic display, especially considering the book’s contents, which are transported into an abstract dimension of reception and perception.

“Mothermilk,” a video work, shows the recurring image of breast milk being poured to a kitchen sink from a baby’s feeding bottle. Breast milk is, literally, an extension of the artist’s body. The repetition with which it is poured to the sink, again and again, its nutritious and maternal potential going to waste, enacts something of a rite of passage or a religious ceremony which signals the untying of the inextricable bond between a mother and her child right after birth – the pain of rupture and separation, the dissolving of a dependency.

With this body of works Goldvicht enters into a subtle and reflective dialogue with feminist art from the 1970s up to the 1990s, a broad and eclectic movement of artists who worked out of a conscious and deliberate feminist worldview. The first distinct wave of what is called “feminist art” dealt with a range of private and social issues, from women’s bodies, their sexuality and vital forces just as their regimentation, to the social mechanisms of oppression at work in both the private and public realms of life (“the personal is the political”) and the resounding absence of women artists from art history; it is an art that, at its most radical, made use of provocative imagery, shock tactics and subversive aesthetics. Golvicht’s art, however, tackles questions of gender in a more subdued manner, putting emphasis on issues related to everyday life in connection to art-making, with both generally taking place within the confines of a domestic surrounding.

It is in this sense that Golvicht draws on a seminal work of feminist art in particular, Mary Kelly’s “Post-Partum Document,” which includes collected material from the early years of a child compiled between 1973–1979. Although the child featured is indeed Kelly’s own son, the focus here is not on his development but rather on an attempt to convey the artist’s experiences and aspirations in the long process of what we call “motherhood.” Kelly, who looks to undermine the generally accepted notion that places creativity and motherhood on opposing poles, gives an outlet to the complicated feelings attached to motherhood – a thematic that found little room for expression in both the general and artistic discourse at the time, and that, to this day, remains limited.[2]

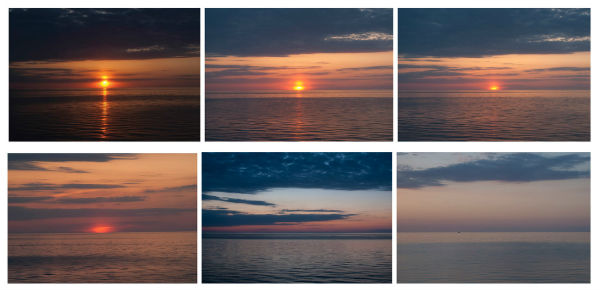

Kelly’s practice of an ongoing and continued documentation is echoed both in “Mothermilk” and in Goldvicht’s “Sunsets,” a series that unfolds through dozens of sunset photographs taken by the artist over the years, since the 1990s to this day. Goldvicht began taking the pictures as a teenager, upon receiving her first camera; this may account for the obsessive attachment to this sentimental subject matter, sometimes associated with teenage romance. First shot on film and later progressing to digital formats, the dozens of photographs in the series formed a rich depository of sunsets – an overly-banal image to begin with, that, once repeated on end, is further emptied of the exalted beauty it supposedly possesses.

A cross between routine and ritual, the repeated iterations of “Sunsets” gradually becomea kind of protective layer, an impenetrable envelope whose blinding – if tacky – beauty, the kind that embodies the clichéd promise for happiness and unending love, seems to shield one from the loneliness and pain lurking beyond the threshold of childhood, to safeguard the promise for a better future, the hopes and dreams of youth. Not originally intended to be viewed by others, this depository of images is exposed in all its elusive pathos. The serial presentation of this private collection, while touching on the intimate longings of a girl coming of age, likewise marks the moment of disillusionment.

Dream and reawakening coexisting side by side is likewise to be found in the back-and-forth movement of “Takeoff”: an infinitely looped video of a plane taking off on a rainy day. A short cyclical loop, it harbors the promise and thrill of the moment of takeoff; and yet, it is entirely clear that the plane is never to reach its destination.

Goldvicht’s work is characterized by an allegorical vocabulary that allows her to touch on private longings and the innermost layers of the experience of self. It is a body of work that digs into dilemmas related to life and death, doing so from a personal point of view while still maintaining the potential for universality. Alongside the clear thematic link to women’s art of former decades, in its therapeutic aspect it intimates that of Joseph Beuys, a German artist associated with the democratization of art and the blurring of lines between art and life. Despite the differences in themes and visual language, Goldvicht’s work presents some marked similarities to him: the incorporation of art into life, the therapeutic values attached to artistic practice, strong autobiographical themes and a rich materiality, often offered as a comfort for charged traumatic experiences. Yet unlike Beuys, whose self-invented autobiographical narrative conditions his position and identity as an artist-shaman in the community – part of a larger project in which the individual body comes to overlap with a collective body in need of healing – it is evident that for Golvicht, in her current works on view, the therapeutic element is activated on a more private and intimate level, one that doesn’t explicitly carry the pretentions for overall wellbeing, but rather functions within the abstract and poetic stratum.

Sally Haftel Naveh

[1]In the Hassidic movement, it is customary to commence the teaching of reading and writing with a ceremony involving the letters of the Hebrew alphabet smeared with honey. The toddlers attending the Heder familiarize themselves with the alphabet by licking the letters.

[2]Tal Dekel, “The Post-Partum Document: The Exception that Proves the Rule,” Gendered – Art and Feminist Theory, Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013, pp. 98–99.