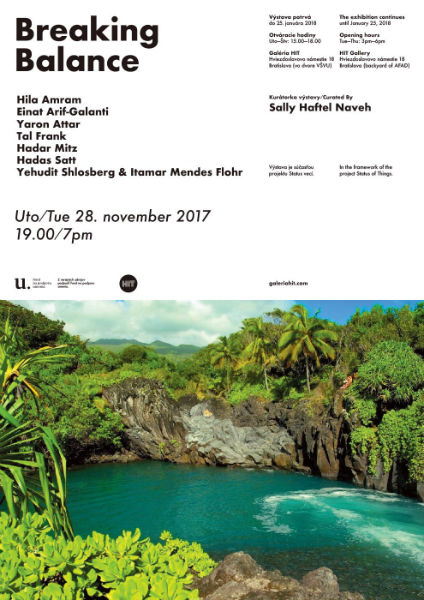

Breaking Balance

Hila Amram/ Einat Arif-Galanti/ Yaron Attar/ Tal Frank/ Hadar Mitz

Hadas Satt/ Yehudit Shlosberg & Itamar Mendes Flohr

HIT Gallery, Bratislava

Nov 2017 - Jan 2018

With the USA’s recent withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord – an agreement signed by 174 countries in an effort to curb global warming according to UN policies on climate change – a withdrawal made citing unfairness and the risk it poses to its coalmining industries and the jobs of thousands, it has become more critical than ever to discuss the charged and tangled relationships between mankind and nature since the dawn of times.

Homo sapiens has been in existence for several millions of years, yet the tipping point in this relationship dates only several centuries back. Fully dependent on nature for their survival, primitive cultures had always lived in awe of nature and its spirits, worshiping them in the hope of living in harmony with nature. An attitude of fear mingled with admiration is manifest throughout the ancient mythologies – from the ancient Greeks to the Celts, Balts and Scandinavian peoples – where the elements of nature are personified through a pantheon of gods that are at once ruthless, shielding and nurturing.

Yet man’s display of awe and subservience began to diminish with the technical progress of civilizations, allowing them to widen their grip on nature and its resources. In fact, for Western civilization, man’s overpowering of nature was seen as a necessary condition for escaping the latter’s uncertainties and threats. This worldview reached its peak with the industrial revolution, a time of man-made exploitation on a massive scale; it coincided with great scientific and technological progress, a sharp rise in life consistency, an unprecedented growth in the earth’s population, and, eventually, with the consumerism and digital revolution we are experiencing today.

According to Horkheimer and Adorno, the rift between man and nature is inherent to the Age of Enlightenment. However, as they argue in their Dialectic of Enlightenment, the same mindset that sought to liberate man from its dependency on nature by exerting control over it, had also resulted in growing control over society itself and its individuals. Hence the overpowering of nature ultimately leads, in turn, to the subjugation of man, to a loss of subjectivity and to a harnessing of every unit of society to a greater economic apparatus. All this, argue Horkheimer and Adorno, can be traced back to the workings of reason.[1]

In today’s dire reality we are able to witness the detrimental impact that we, as humans, have over the planet. A cycle of over-exploitation of natural resources, carbon emissions, urbanization and industrialization on an unprecedented scale has resulted in irreparable damage to ecosystems, extreme weather conditions and a sharp increase in natural catastrophes. Dubbed by some as the Age of the Antropocene, it is a new ecological epoch that can potentially lead to the ‘sixth extinction’ of planet earth.

Breaking Balance brings together a selection of works by Israeli artists who address this perennial clash between nature and culture as has evolved throughout the millennia of human civilization. With an approach going from the critical to the lyrical and whimsical, they address this ongoing tension across its repercussions in nature and the human mindset and activities that, motivated by financial gains and technological progress, lead to irreversible environmental damage.

The works look at the many strategies of subordination, domestication and exploitation with regard to nature and its resources through a range of positions: from the elegiac tone of Tal Frank’s Tie Break: Third Set, which stages a miniature wood from a collection of scorched baseball bats, to the tongue-in-cheek video by Hadar Mitz, Hold the Sun, where a glamour girl stands on a beach, effortlessly exerting her power over the setting sun in a parody of man’s domineering attitude toward to nature.

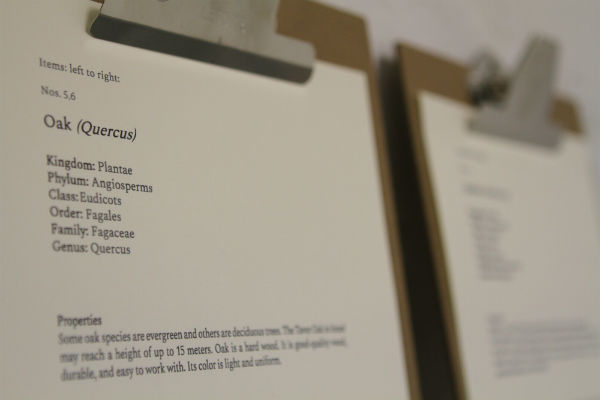

Hila Amram's Regressive Evolution (2017) is an installation comprised of assorted objects from organic and inorganic sources, including household utilities, archeological digs, organic growths and local vegetation. Sourced locally, the different elements are combined using long processes and fermentation on the site, resulting in a vivid surrounding that is both familiar and fantastical. The work process involves varied procedures such as classification, sorting, charting, grafting, controlled experimentation and more – practices that allude to the proto-science of early modernity as to the intuited collecting drive behind cabinets of curiosities.

Amram, who typically works with organic tissues and other assorted materials, acquires her materials locally at urban and natural surroundings. Employing her own ingenious vocabulary on them, she touches on layers of the social and political while raising broader issues related to the polarities between the organic and artificial: nature and technology, our consumerist culture, human intervention in nature and the growing realization that our ecosystems are on the brink of a crisis, endangering whole species and the natural landscape as we know it.

In a work titled Stop Motion (2017), Einat Arif-Galanti confronts nature with artificiality, drawing a line between an artistic discourse and current environmental concerns. A time-based work, Arif-Galanti placed an assortment of fruits and flowers of both organic and synthetic origin in an elegant plastic case. Over time, as processes of decomposition begin to take hold, only the organic elements are affected, with the synthetic ones maintaining their indestructible plastic glow, like the last surviving remnants of a disappearing culture.

In choosing an arrangement of fruits and flowers, the artist references the tradition of Vanitas paintings and Memento Mori. By the same token, she embraces the cautionary message contained in those allegorical paintings, offering a modern reinterpretation to level a critic at the global economy of consumerism and excess which has taken a deep toll on our environment. At the same time, by opting for the immediacy of real-life presentation, she distances herself from the classical values attached to this painterly tradition.

The video work Stoning (2014) by Yaron Attar is like cinematic postcards that bring brief outtakes from the flow of life: a group of children chasing a cockroach at the beach in a resort town in Montenegro, finally getting hold of it and stoning it. Presenting in this bustling outdoor setting a mundane scenario that seem to point to the aimless gaze of a chance tourist.

And yet – as repetitive patterns and a charged air of ceremony begin to emerge – we gradually become aware of the gaze of the artist, an awareness that heightens the dramatic edge inherent in the scene. Even so, the conflict of the drama never fully unravels, leaving us with the ongoing loop of ephemeral moment where the accidental and deliberate merge, instilling a diffuse state of mind between regulated patterns and occurrences and the raw and unforeseeable.

In Tal Frank’s Tie Break: Third Set (2017), a series of baseball bats in varying sizes are arranged in glass display, bringing to mind a rare specimen on view at an ethnological museum. Lined up in a row, each features a black offshoot on its top, which in fact was carved from the very wood of the object. Scorched by a fire that nearly consumed them, they evoke a surviving specimen in the aftermath of a natural catastrophe.

With readymade objects as her point of departure, Frank carved the wood manually, an action that suffused it with a series of tensions and inner contradictions. An emblematic object of Americana, sports activities and leisure, the bat now reclaims its original properties as wood, so much so that it appears to grow branches once more. The glass display that frames this unlikely transformation captures a hybrid, manufactured nature, where an object familiar to us coexists with its surreal metamorphosis. A disturbing image, it channels man’s inferiority as regards the devastating powers of nature.

In Hold the Sun (2016), a video by Hadar Mitz, a glamour girl stands across the backdrop of a beach at sunset. Nearly-static, the frame shows the girl holding sun as it were between her fingers, slowly but steadily lowering it until it disappears in the in the sea. An overwhelmingly clichéed image supposedly manifesting transcendental beauty in nature, the vision of a sunset at the sea is reenacted as a parody of man’s ability to exert control over the elements.

Sporting the body language of someone trying to sell cosmology as a commodity on a TV spot, the girl appears nonetheless capable of wielding power over the sun by the mere touch of her hand, visibly handling the daily recurring marvel of the setting sun. This act of light exertion manifests the work of art as a thing of magic, as a gesture able to subjugate the unruly elements of nature by the means of manual handling.

The digitally manipulated photos in Black Sorrow (2017), Hadas Satt’s photo installation, show images of bats turned upside down. An enigmatic mammal, bats have long been associated with numerous myths and superstitions. Using simple editing means, the series transforms them into acrobats balancing themselves on ropes rather than hanging bellow them. Increased exposure was applied to reveal individualistic facial features, as if in broad daylight. The work takes its title from “la pena negra,” a Spanish expression associated with flamenco culture, designating a state of being consumed with the sorrow of the world.

Aside from the theatrical connotation, the work also references an innovative weapon that the US had attempted to develop against its Japanese opponent in WWII: Bombs containing masses of hibernating Mexican free-tailed bats; once unleashed, these would have wreaked havoc on Japanese housings, typically made of paper and wood. The project was abandoned, however, as bats escaped the testing facility in New Mexico, causing rampant fires. In Satt’s work, the futile attempt to tame nature and subvert it to human needs attaches to the melancholy sentiment commonly associated with the nocturnal creature.

“Journey of a Dead Man,” a film by Yehudit Shlosberg and Itamar Mendes Flohr, documents the four-hour journey of a freight train carrying phosphates from a mine in the Negev to the port of Ashdod and back. Shot from locomotive’s front window, it shows the vast arid landscape of the Negev as it is parsed in the middle by the train’s trajectory – the sole interruption to this unending, pristine desert land. The violence implied by this stark human intervention is intensified in expectation of the Dimona nuclear reactor, which at one time enters the primeval view. It is a presence that, while momentary, taints the journey with an explosive, and politically-charged, potential.

Examining the link between arid, sparsely populated areas and the economy of mass destruction, the work also looks at the subjugation of nature for political ends. As suggested by the work’s title, the linkage to the New Mexico desert – the testing ground of the US atomic bomb, also known as The Manhattan Project – conjures the risk an of imminent doom, such as inheres in human intervention. The slow pace of the train ride, together with the monotony of the desert landscape, produces a tense, hypnotic viewing experience, building up to a cataclysm that fails to happen.

Sally Haftel Naveh

[1]This is the rationale through which Horkheimer and Adorno attempted to comprehend Nazi evil and barbarity, seeing it as the continuation of a chain of events on the historical axis of Western civilization.