Nitzan Satt

I’ve Got a Right Triangle and I Won’t Hesitate to Use It

Umm El Fahem Contemporary Art Gallery

November 24, 2018 - March 23, 2019

In the center of Nitzan Satt’s exhibition, “I’ve Got a Right Triangle and I Won’t Hesitate to Use It,” are three epitomic symbols of Bedouin society: the tent, the well, and the camel. Satt, an artist and architect, invests modernistic thinking in the symbols in order to generate a material and formal transformation that yields specious hybrids that are not free of irony and humor. Thus she tracks the potential of change that is intrinsic to the representational symbols of a minority group that experiences life under a hegemonic policy—a potential also produced by eradication, estrangement, self-censorship, and cultural disparities.

The transformative demarche begins with Satt’s hands-on familiarity with the Bedouin education system in northern Israel via two schools where she has taught art for the past four years. Her acquaintance with the schools also exposed her to the community role that they play as, at times, the only secular public buildings in their villages. As such, the schools undertake to instill the Bedouin heritage, which is dissipating under the weight of lifestyle changes. They go about this, however, in dissonance with the overall planning environment of the school, which projects modernism, alienation, and standardization as required by the Ministry of Education, whose program is applied directly.

Sometimes, however, an attempt to reclaim the presence of motifs from Bedouin society is encountered in an architect’s sincere wish to pour traditional elements into the modernistic language of the buildings. It is these elements, of all things, that give rise to the most fascinating planning moments. When a principal asked to have a well added in a nod to Bedouin courting customs, for example, the architect translated it into what one might call a “well of light,” an abstract element that allows light to enter the building but in practice remains foreign in its form. Another principal asked to give expression to the value of hospitality in Bedouin society by creating an entrance hall that has a community function. Ultimately, however, the idea was relegated to a classroom that was redesigned by having a hospitality tent erected in it, in a way that brings to mind a desiccated vestige. Even if the tent is evoked in various ways in Bedouin public buildings, it is usually an empty and disconnected gesture. So it is even as the real venue of hospitality—the traditional Bedouin tent, still standing next to each family’s permanent house—tends to lose its original configuration and presents itself in the manner of an industrial warehouse in order to comply with zoning laws.

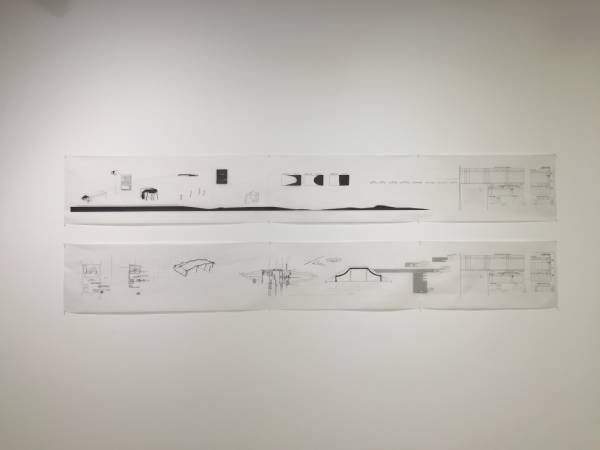

The three works in the main hall of the exhibition show objects that resemble the tent, the well, and the camel—three pillars of the traditional Bedouin way of life, translated here into a language of planning and sculpture that allows these architectural improvisations to resonate. The tent, sketched in the bureaucratic format of a building permit application, uses the contour lines of a standard ID card as the logic that guides its design and plan. The well is converted into a monumental structure composed of segments that are reorganized in accordance with an unfamiliar logic—its opening perpendicular to the wall, like a connection between interior and exterior that in one stroke replaces the muddy soil with the outline of a urban landscape. The camel, set within a downscaled architectural model, soars to the height of a wooden stand, as though it were offered a parking place. “Social Constructivism,”another work presented on the entrance floor of the gallery, combines Bedouin embroidery with the scholastic contents of math lessons as an instrument of empowerment.

Although Satt’s hybrids of sculpture and planning appear to disrupt their objects, they correspond to the hybrid spatial identity that typifies Bedouin localities in northern Israel, the outcome of zoning policies produced largely by elements external to the community. In the absence of a probing architectural discourse about the transformation that Bedouin society is undergoing, the cultural symbols remain integrated into the structures as contentless shapes or, at the most, abstractions neutered of all function. In her works, Satt wishes to raise questions about the role of architecture in preserving and destroying a social and political narrative in a way that will shed light on the status of the Bedouin within the balance of forces in Israeli society.

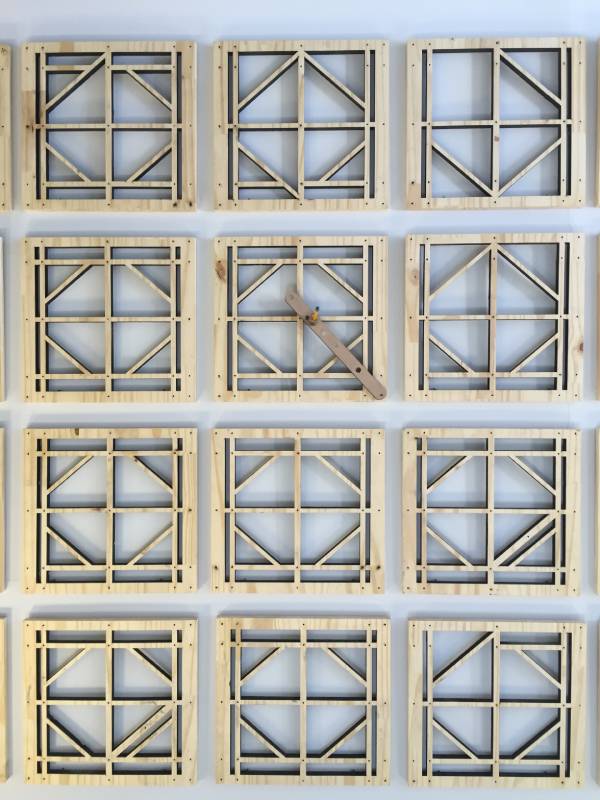

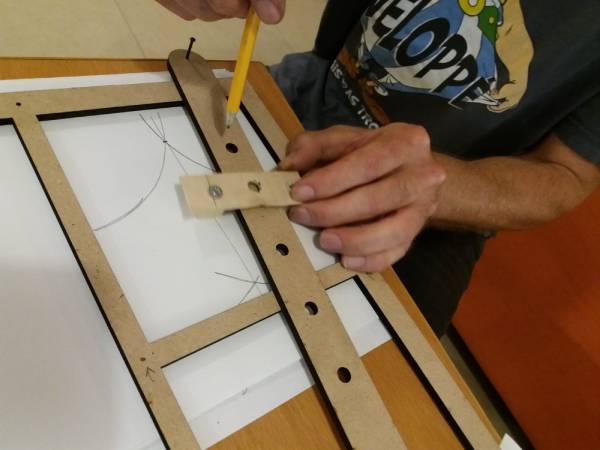

“Social Constructivism,” part of Nitzan Satt’s solo exhibition “I’ve Got a Right Triangle and I Won’t Hesitate to Use It,” presents a modular sculptural array composed of thirty-five wooden frames that are meant for educational activity, each internally divided on the basis of an ornamental scheme flowing from the embroidery of a Bedouin dress. When the frames are taken down from the wall, the students attach a large wooden dial to each that helps them to solve geometry problems. Their answers are sketched on a piece of paper that lays atop the frame in a way that yields a traditional embroidery pattern. The work is an example of “ethno-mathematics,” a practical method of teaching geometry on the basis of methods of calculation that ethnic groups use at various levels of daily life.

Mathematical calculation is intrinsic to embroidered ornamentation in traditional Bedouin dresses. By linking math problems to the example of ornamentation, the work serves as a vehicle of social empowerment for children and youth in Bedouin society and in Arab society at large—groups that suffer from a tracking policy that fails to take account of their cultural heritage and inhibits their participation in math-intensive subjects. Satt’s aim in this exhibition is to set in motion a discussion over zoning practices in Bedouin localities. She wishes to enhance awareness of the public sphere in the hope of inducing young people, too, to get involved in the matter—particularly given the dearth in Israel of Bedouin architects who can create culturally adjusted buildings.

Sally Haftel Naveh